The two Israeli soldiers standing guard at the entrance wave us through the large yellow gates so familiar to Israel’s kibbutzim, and we drive into Sasa, a village high in the western Galilee and a microcosm of Israel’s north.

Five hundred people lived here in peacetime, now only 13 remain, the rest gone under a mandatory evacuation order from the government.

In all, almost 100,000 Israelis have been forced to leave their homes along the border and are now living in hotel rooms around the country.

At the top of the hill we walk cautiously past metal barriers and warning tape, cautioning against what is beyond: southern Lebanon, Hezbollah-controlled Lebanon, barely a kilometre in front.

The actual border itself is rarely visible, hidden behind the rolling hills, occasionally emerging as it zigzags along the contours, still the subject of dispute 18 years after the last war, in 2006.

Under a United Nations resolution that followed the ending of that conflict, a demilitarised buffer zone was agreed, between the Blue Line of UN barrels that marks the unofficial border and the Litani River which runs between four and 20km from the Israeli border.

Hezbollah has breached that, positioning its fighters and building posts close to Israeli territory. Only last September, when we were filming a report on the increased tensions then, I saw Hezbollah fighters literally yards from IDF soldiers along the border.

Israel points out this is a clear violation of UN law and must be corrected – it is being used to legitimise its daily bombardment of Hezbollah in recent weeks. UN peacekeeping forces in southern Lebanon are largely ineffective and powerless to intervene.

One of the kibbutz leaders, Yehuda Livne, has remained along with his wife Angelica to protect the community and make sure essential work can still be done, like the recent apple harvest.

Read more:

Could Israeli escalation with Hezbollah lead to a wider war in the Middle East?

‘We did it with our Arab friends’

“We recently finished, every apple picked, and we did it with our Arab friends,” Angelica tells me, smiling. “Three thousand tonnes!”

Northern Israel, unlike many parts of the country, is characterised by the largely peaceful coexistence of Jews, Muslims and Christians. It’s something they’re proud of.

Yehuda then points out a crater in the orchard below, where a Hezbollah rocket landed. The kibbutz, like many along the border, has been in the line of almost daily fire since 7 October.

A few weeks ago, the school auditorium took a direct hit from an anti-tank missile – the use of these weapons has become more regular since Israel pushed many Hezbollah fighters out of the range of guns, but unlike rockets, which fly in an arc, anti-tank missiles have a flatter trajectory and so are difficult to shoot down with the Iron Dome defence system. And they’re accurate.

The auditorium is a mess. Windows blown out, a heavy metal door twisted from the explosion and smoke scars up the walls. What would have happened had the school been open doesn’t bear thinking about.

Read more:

Netanyahu rejects US calls for Palestinian state

Hamas video appears to show bodies of two hostages

‘It’s a small war’

Yehuda and Angelica have moved house, a little further back and out of the firing line. They sleep in a small, dark safe room on the ground floor, the window covered by armoured sheeting and an emergency filtration system installed to give them clean air in the event of a chemical attack.

“There is a war because every day they’re shooting and we’re shooting back, so actually there is a war also in the north, but it’s not a big war, it’s a small war,” says Yehuda.

Like many kibbutz residents, the Livnes are lightly political and want peace with their Arab neighbours.

“What will be the future if all dream of peace and dialogue is finished?” Angelica asks. “I don’t want to believe it’s finished.

“What can we do? What can I do to speak with them, to explain to Palestinian people that we want to be together? That there can be two states you know, and we can help each other because there is so many intelligent people, so many good people. Why, why, why do we have to fight?”

‘The feeling is that we’re being hunted’

For many here, safety won’t come with the end of missile attacks, it needs to be more than that, a permanent change in the status along the border.

“The feeling is that we’re being hunted,” says Sarit Zehavi, the founder and president of the Alma Research Group, a non-governmental organisation that monitors and analyses Hezbollah.

“Hezbollah wrote the plan that Hamas executed, and it could happen again. Here, you hear the war all the time.

“We can no longer trust our understanding of the intentions of the other side. We can only trust the elimination of the threat, and the threat by Hezbollah is bigger than the threat by Hamas.”

Life cannot return until Hezbollah is pushed back

If people here are undecided whether they want a war to force the issue or diplomacy to prevail, they are unanimously clear on one thing: life cannot return until Hezbollah is pushed back, far enough not to be an immediate threat.

Hezbollah is thought to have a tunnel network much bigger and more sophisticated than Hamas’s in Gaza. It runs deep under the hills around the border, popping up within metres of Israeli villages.

Residents of northern Israel are now worried Hezbollah will come across the border, like Hamas did on 7 October.

“I don’t have any ideology about war or peace, I want the effective way,” Sarit tells me. “If we find a way to do it peacefully, fine. The problem is that Hezbollah will not do that.

“So if you find any diplomatic solution that takes the rockets out of the homes of the Lebanese, one home after the other, and will block all the tunnels, one tunnel after the other, okay.

“If you find an international force that can do that, fine. But until today, it hasn’t happened.”

Hezbollah will remain too close for Israel’s liking

With many of the villages evacuated and the military already on a war footing, there are some senior Israeli politicians and commanders who believe now is the moment to invade southern Lebanon. There will be no better opportunity to change the dynamic once and for all, they argue.

A war with Hezbollah would be difficult though, and extremely bloody for Israel. Hezbollah is much better armed and better trained than Hamas. Its fighters have recent battle experience in Syria and its arsenal is thought to be in excess of 150,000 missiles, some of which can reach the southern tip of Israel and strike with precision.

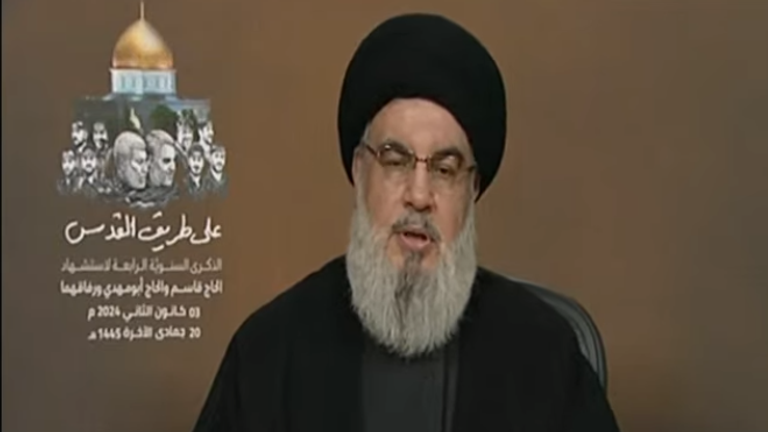

Hassan Nasrallah has been open about where it would target – Israel’s government buildings, the main airport outside Tel Aviv, electrical plants and water works. Such is its firepower, it could potentially overwhelm the Iron Dome system.

If there was a ceasefire in Gaza, Hezbollah might stop its attacks on Israel, but it will remain on, or close to the border. Too close for Israel’s liking.