Retail ownership grows in first quarter, banks fall

The municipal bond market expanded in the first quarter of the year as ownership by households, mutual funds, foreign investors and life insurers rose, but U.S. bank ownership of municipal securities fell, the latest Federal Reserve data shows.

The first quarter of 2023 has been regarded as a markedly better start than 2022 and that performance has led total market value to increase by 1.9% to $3.945 trillion.

The total face amount of munis outstanding was up only 0.1% quarter-over-quarter, as it rose $3.9 billion to $4.02 trillion.

Moreover, the average price of outstanding munis is now 98 cents, up from 96 cents in Q4 2022. This is the second straight quarter of recovery, said Matt Fabian, partner at Municipal Market Analytics.

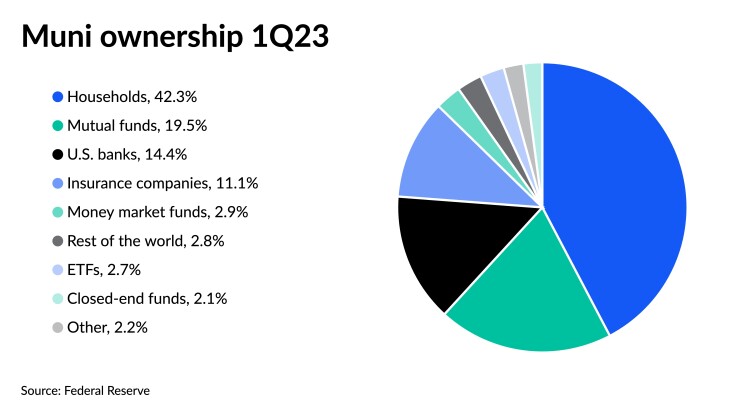

Household ownership of individual bonds — which includes direct ownership of individual bonds in brokerage accounts, fee-based advisory accounts or separately managed accounts — continued to be the largest category of muni ownership at 42.3%. Household ownership of munis rose $58.8 billion, or 3.7% quarter-over-quarter, to $1.669 trillion.

Mutual funds owned 19.5% of the market, growing 3.2% from Q4 2022, or $23.9 billion, to $769.7 billion.

Foreign investors saw their ownership of munis rise 2.8%, or $3.4 billion, to $112.4 billion. Foreign investors account for 2.8% of muni ownership.

U.S. banks, which accounted for 14.4% of individual bonds in the first quarter, saw their ownership of muni securities fall. U.S. banks owned $566.7 billion of munis, down $13.3 billion or 2.3% from Q4 2022.

Insurance companies — both property and casualty insurance and life insurance — had 11.1% ownership of individual bonds. The category was relatively flat quarter-over-quarter, falling by just 0.1%.

The data “reinforces some of the trends that we’ve been seeing: the shift out of mutual fund ownership into SMAs and the divestment by the banks and insurance companies because of the lack of value in munis,” said Pat Luby, a CreditSights strategist. “The big takeaway is the continued ebbing of insurance companies and bank exposure in the market.”

For individuals, though, the positive first quarter made it “easier for financial advisors or investors to stick with their plan and not feel like they should try to time the market,” Luby said. “Things have gotten bumpy since then, but the first quarter, on the whole, was constructive for investors.”

For the most part, the muni market recovered in Q1 2023 “after a difficult 2022, generating total returns just under 3% [and] the holdings of most investor groups increased, supported by marked-to-market gains, as well as some buying,” noted Barclays strategists Mikhail Foux, Clare Pickering and Mayur Patel.

“The muni market has been stable to positive this year, and that has been through household buying, probably of SMAs, and through more traditional household platforms,” Fabian said.

Institutional investors “treaded water ahead of the debt ceiling crisis, amid the Fed raising rates, and with a notable lack of liquidity because of uncertain momentum everywhere in the muni space,” he said.

Fund growth

Anecdotally, Luby said, there is evidence of investors moving into SMAs from mutual funds. However, mutual funds still rose $23.9 billion, or 3.2% quarter-over-quarter, to $769.7 billion.

“Mutual funds operate in a semi-closed environment — the mutual fund platforms — so it’s not unusual for investors to move money between asset classes and standard mutual funds,” Luby said.

However, he said, it takes more of an effort to move out of mutual funds and into SMAs.

Despite this movement from mutual funds to SMAs, Fabian does not think mutual funds are “dead by any stretch.”

“They’re being forced to compete on fees primarily and being forced to roll out new [exchanged-traded funds] and passive, low-cost structures in the fight for assets,” he said. “But it’s likely mutual funds will remain a dominant institutional demand factor in our market.”

Any performance at this point, Fabian said, “lives and dies based on mutual funds and there’s no reason to think that that’s changed.”

David Litvack, a tax-exempt strategist at the chief investment office at Bank of America, said it was “somewhat surprising to see mutual funds increase their holdings because the flow data has been mostly negative,” but noted it appears it was predominately the result of an increase in market value.

Mutual funds saw inflows of $2.292 billion in January, but outflows of $2.221 billion in February and $1.390 in March, according to Refinitiv Lipper. In Q1 2023, there was $1.319 billion of outflows, Lipper data showed.

Outflows from mutual funds continued from there. Lipper reported 16 straight weeks of outflows since mid-February before investors added $460 million of inflows this past week.

“Demand is still somewhat weak given the flow data, but it appears that’s been offset to some extent by inflows into SMAs and if we see yields start to come down you’ll probably see more of an interest for the funds,” Litvack said.

Banks fall

“Banks were in the eye of the storm that started in mid-March, and their holdings declined … in Q1 2023” by $13.3 billion and will most likely decrease further in Q2 2023, the Barclays strategists said. Bank ownership of munis decreased 2.3% to $566.7 billion in the first quarter.

This Fed data further supports Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. data from Q1 2023 that showed banks were rapidly owning fewer munis, Fabian said in a report in May.

That was “the largest quarterly decline in aggregate bank holdings of municipal securities (not including direct loans) since at least 2003 with institutions eliminating $17.2 billion of bonds from a market value perspective,” he said.

Bank municipal securities portfolios in Q1 2023 were $366.8 billion, the smallest since 3Q 2020, per FDIC data.

The quarterly change “was worse on a cost basis, down by $21.3 billion, suggesting that, for the third quarter in a row, banks have either sold municipal holdings or let their portfolios shrink via runoff,” Fabian said.

“Just like the FDIC data showed, banks do appear to be starting to reduce their exposure to munis,” he said. “That’s a slow, but probably steady trend.”

“Banks bought a lot of munis during the pandemic years when interest rates were low, took a lot of losses at those low-interest-rate investments last year, and are now slowly backing away from the sector,” Fabian said.

He expects this trend to continue over the next few quarters and would not be surprised to see banks “down by another $50 billion by the end of the year.”

Fabian said the recent banking crisis, which started with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in mid-March and continued with the failures of several other regional banks, was a symptom of this.

“Banks that built up large muni positions during the pandemic generally took large losses from those positions, because of the Fed [rate hikes] last year and this year,” he said.

“It makes sense that they would be more cautious with their munis going forward,” he said.

Luby argued the recent banking woes were not a huge factor in the drop of municipal securities by banks.

However, he said, as banks have “munis maturing, they can’t justify reinvesting in munis unless they can get taxables, and taxables have been in very short supply.”

On a relative value banks “can’t justify tax-exempt munis at current levels,” according to Luby.

“That will continue even if we get total stability from all the banks going forward,” he said. “I don’t see their appetite returning to tax-exempt bonds.”

Supply/demand components

The Federal Reserve’s data for Q1 2023 is mostly unsurprising based on what’s “happened with both supply and demand in the market,” said Matthew Gastall, executive director and head of Wealth Management Municipal Research and Strategy at Morgan Stanley.

“When we take a look at where municipals are trading versus some of their taxable counterparts on the household side, needless to say, that helps taxable instruments to become more appealing to low- to mid-tier federal bracket investors and low-tax state participants,” he said.

“For banks and other types of institutional entities,” Gastall said, it also helps to “encourage a focus on different types of taxable instruments because they’re appealing on a tax-adjusted basis.”

“If that supply-demand imbalance we’ve been experiencing reverses, that could potentially change,” he said.

As the summer months approach, Gastall said, there will be more than $100 billion of redemptions from June through August.

At the same time, supply averages from 2000 to 2022 posted an approximate 30% decline in issuance between June and July.

“We’re in the middle of the pre-summer supply ‘push’ and interest rates are higher than they were a month ago. Consequently, we’re questioning whether this is ‘as good as it gets’ for this particular economic cycle for municipal investors,” he said. “The supply-demand imbalance might be exacerbated as we move into the summer, while continued inflationary progress and/or slower growth may lower ‘belly’ and long-end rates in the second half of the year.”